Archive

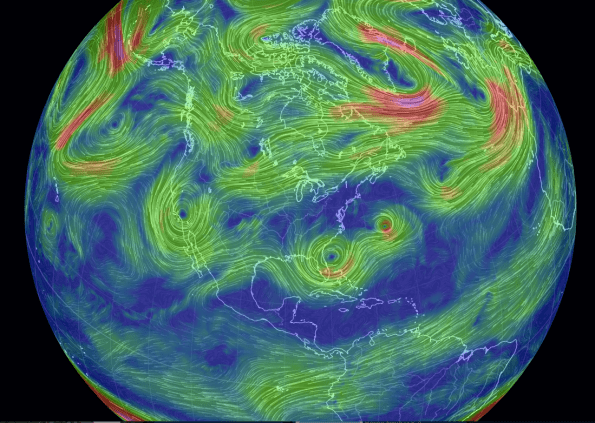

Today’s weather ~ visual

An eye on western Colorado weather

Shirt tales from an early visit to Marsuret Azienda Agricola

Alessio Marsura of Marsuret Azienda Agricola shares his family’s prestige Cartizze Prosecco DOCG on a cool spring day in Valdobbiadene. Marsuret makes a full line of Prosecco but only five DOCG, all reflective of this extraordinary area.

The advent of the grape harvest (and the “everything else” harvest) in western Colorado reminds me how the hopes of spring and efforts of summer come to fruition in autumn.

Last spring, as is habit, I was in northern Italy’s Veneto, the heartland of Prosecco DOCG where in a steep-hilled triangle roughly denominated by Valdobbiaddene, Conegliano and Vittorio Veneto some of the world’s best sparkling wine is made.

Two days earlier I had left Verona and Vinitaly and now was enjoying the view from top of the Marsuret winery in  Valdobbiaddene with Alessio Marsura, who was explaining to a couple of visitors the lay of his family’s vineyards.

Valdobbiaddene with Alessio Marsura, who was explaining to a couple of visitors the lay of his family’s vineyards.

Marsuret Azienda Agricola was founded in 1936 by Alessio’s grandfather Augostino Marsura (Marsuret is a family nickname) and nearly 80 years later the family continues to produce award-winning wines in the heart of the most-prestigious of the Prosecco DOCG zones.

Despite also still recovering from the hectic experience that is VinItaly, Alessio said he was enjoying the quiet of the surrounding vineyards as he graciously shared his family’s Superiore di Cartizze Prosecco DOCG.

“From here,” he said, turning toward the still winter-brown hills, “You can almost see the vines where this wine is grown. It looks better in the summer, of course, but this gives you an idea of the difficulty of growing grapes in such steep area.”

The he turned.

This denim shirt, made in by Crawford Denim & Vintage Co., is hand-dyed with the Robert Mondavi Heritage Red blend.

“We make only five of our Valdobbiadene DOCG Proseccos and during the fair (VinItaly) someone called them ‘cult wines’, ” he said with a laugh. “Like your shirt.”

At the time I was wearing a wine-dyed jean shirt from Robert Mondavi and he was referring to article from the Vinitaly press corps that said the deep-indigo shirt was one of “two cult objects to be worn” during the fair.

The shirt, made by the Crawford Denim & Vintage Co. of Manhattan Beach, Cal., is hand-dyed with the Mondavi Heritage Red blend and features wooden buttons made from wine barrels.

Alessio turned away to look at the bare vines, and said the promise of summer seemed a long way off.

“There is much to be done between now and harvest, it’s barely spring,” he said. “So maybe it’s a good time to drink good Prosecco and get ready for a summer’s work.”

Cork: A New Understanding Of What Is Behind Every Stopper

The well-traveled author Susannah Gold this week is in Sardegna, the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea (Sicily is the largest) and as she notes in this post, home of Europe’s second-largest cork factory. Enjoy.

I have the good fortune to be in Sardegna as I am writing this. A magical and mysterious land, I think of it as a place of beaches, crystal blue water, rocks, sun, sheep, silence, Vermentino, Cannonau and Pecorino,. What I didn’t know was that it also has the second largest cork factory in Europe after Amorim. I once interviewed the head of that Portuguese company but I have never had the opportunity to visit a factory – until now.

Italy is one of the most important producers of cork in the world. Of the 2.2 million hectares of cork forests, some 225,000 of them are in Italy, 90% of which are in Sardegna and the other 10% in Sicily, Calabria, Lazio, Tuscany and Campagna. The wine industry is without a doubt the largest client of the cork industry and uses 70% of Italy’s total cork production.

While some countries…

View original post 326 more words

Colorado grape growers are ‘thisclose’ to big harvest

As anyone with a backyard garden can attest, that cool and wet weather we enjoyed in May, dubbed “Miracle May” by some water watchers, left most of western Colorado about a week to 10 days behind the regular time when it comes to harvesting fruit and vegetables.

Naomi Smith, right, of Grande River Vineyards pours a glass of wine for one of the more than 6,300 guests attending Saturday’s Festival in the Park, part of the 24th annal Colorado Mountain Winefest, at Palisade’s Riverbend Park.

The same is true for grape growers, many of whom this weekend said they still are waiting for their grapes to ripen fully.

The wet spring following a mild winter was very good for the crop, which appears to be one the best in recent years.

“We’re a little behind but all of the fruit looks great,” said John Behr of Whitewater Hill Winery on 32 Road. “It’s really nice to be able to drive down the rows and see bunches of grapes.

“I could get spoiled.”

Deep winter freezes and late spring frosts repeatedly have sliced into the area’s grape crop since 2011, leaving many winemakers, particularly those who prefer to stay 100-percent Colorado grown, to cast an anxious eye at their dwindling supply of available wine.

“I’m down to eight wines and I usually make 17,” said Nancy Janes, Behr’s partner and the winemaker for Whitewater Hill. “So I’m really glad this year came along.”

Janes and a few other growers already have picked some early ripening white-wine varietals but most growers said their grapes need at least another week or so of warm, late-summer days and cool nights to fully develop the desired levels of balance between sugars and acidity.

John Garlich of Bookcliff Vineyards said his grapes in the Vinelands area south of Palisade were about 10 days out from harvest and John Barbier at Maison La Belle Vie Winery in Palisade said his are at about the same stage of development.

Still, Barbier said he’s eager to take full advantage of a big harvest.

“My reds are getting a bit short so this year will be very good for us,” he said. “I want to stay 100-percent Colorado and refuse to buy (out-of-state) fruit, so I can use a good year.

“I think this year I will make some extra cases of wine because I know I can store them and they only will get better with time.”

Jenne Baldwin-Eaton, winemaker at Plum Creek Cellars, said everything was moving along almost on schedule until veraison and suddenly the speed down-shifted.

“I already got some early Chardonnay from Kaibab (Sauvage) and everything else was about normal,” she said. “But after veraison things are little slower and taking a bit longer to get ripe. I can’t explain it.”

Naomi Smith of Grande River Vineyards said she was anticipating a big crop and that Grande River winemaker Rainer Thoma was ready for “things to pop.”

“I think everything is going to ripen all at once, just like the cherries and peaches did,” Smith said. “I think this is going to be a good year for us and other growers.”

Winefest takes new tack on crowd control: Cap those tickets

With an eye on making sure Colorado Mountain Winefest’s Festival in the Park remains a consumer-friendly affair, general-admission tickets to this year’s sun-sprinkled event were capped at 6,000 plus the 350 tickets to the VIP tent.

Procrastinators beware: Late arrivals to Saturday’s Festival in the Park, the signature event for the annual Colorado Mountain Winefest, were stopped by a sign near the front gate announcing “Event sold out.”

What? Sold out?

How could that be?

For the first time in the event’s 24-year history, ticket sales this year were capped. While a cap of 6,000 tickets (plus the 350 VIP tent admissions) into tree-shaded Riverbend Park might not seem like much, you couldn’t get one if you waited until Saturday morning.

“We sold out late yesterday,” said Cassidee Shull, executive director for the Colorado Association for Viticulture & Enology, during a brief interlude Saturday prior to the gates opening. “We sold out of everything – the dinners, the wine bus, the VIP tent.”

That eye-catching red-and-canary yellow at the front gate warning “No Tickets Available” revealed how much this event, again this year sponsored by Alpine Bank, has grown in its two-plus decades and was a very public announcement that Colorado’s most-populer wine-oriented get-together no longer strictly is a local event.

“We really want to people to pre-plan their Winefest,” said Shull, reflecting the oft-heard comments about potential over-crowding. “If we can get them in the habit of buying their tickets ahead of time, it will keep this a fun experience for everyone.”

Shull said last year’s record attendance at Winefest fell just short of 6,000, a level that seemed just about the max in the comfort zone for both wineries and attendees.

At times, particularly during the mid-day crush, the lines at the winery booths get long and a bit pushy as winelovers, helped along by a little inebriation augmented with a bit of dehydration, jostle for their favorite pours. Putting a lid on tickets sales may help keep some of the crowding under control.

Next year’s Colorado Mountain Winefest, the 25th annual, is set for Sept. 15-18. Just sayin’.

Message in a bottle: Natale Verga’s take on affordable Barolo

So who is Natale Verga?

If you guessed an Italian winemaker you’d get credit for being mostly correct.

But there’s more.

I first saw the name Natale Verga, a winery in Cermenate, a small (9,000 population) commune in the Province of Como in northern Lombardy, while gazing at the Italian section in my local wine shop.

I was looking for an affordable Barolo, an oxymoron in most cases, and my eye was caught by Verga’s straightforward label, which simply reads “Barolo,” the winery and the vintage. Hanging from a shelf-talker was the price, a very modest $19.99.

That’s about $16 less than the next-closest price and way below what many other Barolo DOCG winemakers are asking.

On the shelf below was a similar label reading “Barbera D’Alba,” this one a DOC priced at $13.

Natale Verga is the current proprietor of the family owned winery founded in 1895 by Giancarlo Verga. Information even on the website is scant, but this much is available: The winery is huge and typically modern, with lots of shiny stainless steel and the capacity to handle 25,000 bottles per hour.

Thanks to seven different labels and multiple wines (the Natale Verga label includes 21 different wines), aggressive marketing and multiple investments in new technology, the wines are distributed in more than 30 countries.

A video on the website, narrated by Natale Verga, tells an interesting story of the 120-year old winery but oddly skips over what Verga’s monologue refers to as “difficult challenges” and unexplained “unfair play,” apparently from competitors.

“Today we are facing a new challenge,” Verga says in the video without bothering to elaborate. Then he affirms, “We will overcome any difficulties” and goes on to thank some employees who stuck around “when it would have wiser to leave.”

With that cryptic remark, what Natale Verga has overcome is the price hurdle of an affordable and quite delicious Barolo and Barbera D’Alba.

Notes: Natale Verga 2008 Barolo DOCG (current vintage is 2010), $19.99, purchased. Notes of roses, blackberries, dark plums.

Natale Verga Barbera D’Alba DOC, $12.99, purchased. Mocha, dark cherries and raspberries.

Changing the way we find the right wine

There is an ocean of wine out there and at times it can be daunting. This wall of Chianti Classicos was on display this spring at VinItaly in Verona. There about 600 members in the Chianti Classico Consortium.

Last week at Fisher’s Liquor Barn I saw what’s becoming a rare sight: A person pacing back and forth in the California Cabernet aisle, apparently overwhelmed by the hundreds of wines available.

What’s rare about this is not what the customer was doing, since we’ve all spent our share of time looking here and there and not quite finding what we want, but the manner in which she was doing it.

Not a cellphone, iPad, mini-tracker or any of the other online wine guides was in sight.

Instead, she was looking for wine in all the right places: On the shelf and, shortly, in the good company of Rick Rozelle, the store’s wine buyer and resident go-to wine guy.

There are scads of wine guides available (just Google “wine guide”) online and in nearly every newspaper and glossy magazine you’ll see a wine columnist offering his or her breathless advice.

Learning about wine used to be personal: Just you or a small group of friends, going one-on-one with your wits and a bottle of wine.

But that’s all changed, says author Jancis Robinson in a recent article.

But that’s all changed, says author Jancis Robinson in a recent article.

Thanks to the cellphone and the multitude of wine-specific apps at your fingertips, “screens, not books or newsletters, now provide the world’s wine lovers with easy ways to make buying decisions.”

And it’s not just at home but as common in restaurants, bars and liquor stores.

“I used to see people come in here every week with the wine section of the New York Times but now they all have their iPhones out, tapping away,” Rozelle said recently. “There’s way too much information out there.”

As Robinson notes, there are apps for scanning labels (Delectable and Vivino), websites that compare prices, availability and DYI wine reviews (Winesearcher.com, About.com) and even websites for novices (wine-4-beginners.com).

“It is not surprising that today’s armies of wine consumers feel bold enough to share their opinions of those wines,” Robinson said.

To her dismay, Robinson is finding her voice and her 40 years of experience tasting and writing about wines getting lost in the maelstrom.

“I am increasingly aware that my voice, once one of just a few, is now one of an army of wine lovers confident enough to voice their opinions,” she writes. “I would honestly be delighted if every wine drinker felt confident enough to make their own choices … But I do recognize that for many people it will always be simpler to be told what to like.”

It’s easy to take part in what Italian wine expert Alfonso Cevola calls the “Babel standard.”

“It also speaks to how we get our information and what kind of currency we subscribe to (regarding) perceived expertise, whether it be a recognized one or one among our peers,” Cevola writes. “I find also the aspect of trust plays into this.”

Ah, yes. Trust. Which is what you build when you find and use that source of expertise. It might be in some shiny magazine or the online video, but it’s often just as easy, and more reliable, to find a salesperson who makes the effort to know you and your taste.

It takes time, but maybe not 40 years.

Which is why, once Rozelle asked the young lady what she had in mind, it took him but a few minutes to have her smiling and moving toward the check out counter, the right wine in hand.

Vines on a mountain: Elevation as terroir in Colorado winemaking

The concept of terroir, says winemaker Warren Winiarski, includes all things not man-made. In Colorado, that includes growing grapes at high elevation. These Gewurtztraminer vines, thriving at 6,200 feet elevation near Paonia, Co., are among the highest vineyards in North America.

The question of whether Colorado wines reflect a unique terroir has no easy answer.

Supporters of “terroir” – the concept that the place a wine comes from is reflected in its taste and determines its quality – claim they can identify a wine’s distinct origins simply by blind-sampling the wine.

Do Colorado wines reflect their provenance and is it enough to be unique?

For some ideas and possible answers I turned to Warren Winiarski, the winemaker who produced the 1973 Stag’s Leap Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon, the wine that won the 1976 Judgment of Paris and made America a wine-drinking country. Before that, however, Winiarski in 1968 helped Denver dentist Gerald Ivancie set up Colorado’s first modern commercial winery.

During a mid-May tasting of Colorado wines at Metropolitan State University in Denver, Winiarski said how impressed he was with some of the samples. Read more…

In search of a unique terroir

As Colorado wineries mature, they have become more comfortable with making wines that reflect their places of origin. Photo taken at Stone Cottage Cellars, Paonia, Co., elevation 6,200 feet, the second highest elevation vineyard in North America.

One comment you once would hear with regularity at any of the tasting rooms around Colorado wine country would come when a visitor put down his or her glass to remark, “Well, this doesn’t taste like a California Cabernet Sauvignon (or Pinot Noir or Chardonnay or whatever was being poured at the moment).”

While at times such comments were taken as a put-down of high country wines, winemakers today simply shrug, smile and say,”Yes, isn’t it nice? It really tastes of Colorado.”

The winemakers and tasting room attendants may stumble a bit when asked “What exactly does Colorado taste like?” since there’s really no universally accepted definition of what makes a specific wine taste the way it does.

Most of us fall back on the French word “Terroir” to cover a multitude of possible answers, none of which may the sole reason for a wine’s individuality.

Wine writer Jamie Goode on his blog Wineanorak.com said terroir “consists of the site or region-specific characteristics” of a wine.

And the well-respected – if a bit wine curmudgeonly – Jeff Siegel, in a well-done post on his blog, generally commits to saying terroir “includes not just a region’s soil, but its weather, tradition and history.

But is all that what makes a wine identifiable with place?

If you don’t know the traditions (sociologists spend their entire careers learning local customs and traditions) or the history or the weather, can you even mouth the word terroir and get away with it?

Colorado winemakers (just like those everywhere) would love to find whatever it is that identifies a wine from the Centennial State. What makes a Chilean Cab different from a Napa Cab, or an Argentina Malbec differ from a Cahors Malbec?

We know they don’t taste alike, but the differences go beyond the simple storage or transportation conditions.

When acclaimed winemaker Warren Winiarski was in Colorado recently for the Governor’s Cup wine competition, he frequently commented about the importance of a winemaker’s intent and vision (I am indebted to state enologist Stephen Menke of the Colorado State University Research Station for his notes).

Winiarski’s proposition was that while terroir plays a big role, the end result also depends on what the winemaker does with the grapes he gets, a sort of vinous “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

“You can’t help making regional wines,” Winiarski said to Kyle Schlachter of the Colorado Wine Press blog. “That’s the region (substitute ‘terroir’) they’re grown in. They will betray their origins some way or another.”

“Betraying your origins” sounds like terroir.

When wine writer David White of The Terroirist blog wrote that terroir is “omnipresent in wine marketing,” he was not being complimentary.

It’s over-used, White said, “to signify the relation of wine to soil and climate where that relation is essentially uninteresting (and sometimes) used to obfuscate the hard reality of overt flaws like Brett infection.”

What’s more, he said, “The vast majority of claims made about terroir in the wine world are, frankly, bogus. This does not in any way mean, however, that terroir is not an ideal worth pursuing.”

When I first started getting serious about Colorado wine, I had the feeling that many Colorado winemakers were trying hardest to re-create that special wine which may have sparked their initial interest in winemaking or simply trying to satisfy a market that had nothing on which to base a definition of Colorado wines except wines from elsewhere.

Those days are over, for the most part, helped greatly by winemakers gaining two decades of experience in the vineyards and with the grapes they were getting.

We’ll talk more next time about what makes a Colorado wine a Colorado wine.

Grape vines pushing out in the new-found heat of summer

The sudden burst of tropic heat arriving in mid-June was just what Colorado’s wine-grape growers were waiting for.

New tendrils on a Merlot vine at Whitewater Hill Vineyards. The long tips show vigorous growth but they are starting to brown, indicating the plant is turning more energy to fruit production and not new growth.

A cool and wetter-than-normal May restored ground moisture to the point many farmers just now are turning their irrigation water into the vineyards and the awakening plants took advantage of the wet conditions to store energy for the summer growing season.

Now that growing season has arrived.

“This is fabulous,” said an obviously pleased Nancy Janes of Whitewater Hill Vineyards and Winery on 32 Road near Grand Junction. “We’re a little behind in development but that’s nothing to worry about, we’ll catch up during the summer.”

On the other side of Grand Mesa, Yvon Gros of Leroux Creek Vineyards was saying his vines of cold-hearty hybrids Chambourcin and Cayuga are redolent with tiny yellow flowers, a sign of a very healthy crop.

“I was walking through the vineyard today and I stopped because I could smell something,” he said. “It was the florescence, the flowering of the vines. It’s a sign that the plants are gearing up for the growing season.”

Gros and his wife Joanna were taking a brief rest during the winery’s Friday dinner marking North Fork Uncorked, a wine-centric celebration of the West Elks AVA, and Joanna paused to remark about how vibrant the vineyard is.

“It’s been years since I’ve seen it so green,” she marveled and pointed to the long, emerald ribbons stretching downslope in front of the inn. “Yvon has been working hard in the vineyard and now this is the result.”

A young cluster of flowers and tiny new grapes. By summers end, given favorable conditions, the cluster will ripen evenly.

When I asked Nancy Janes if the near-constant rain in May was a drawback, she said there initially was some concern about powdery mildew, something moister climates deal with on a regular basis but something seen infrequently in dry western Colorado.

“Wet weather like that isn’t common here but it’s not something we can’t deal with,” she said. “But the plants really are happy to see it warm up.”

Yvon Gros said his vines were “growing like crazy” in the sudden heat.

“Some of the tendrils are 4 to 6 inches long,” he said with delight.

In the vineyard at Whitewater Hill, Janes clutched a vine to show a visitor delicate tendrils of new growth, soft green curls stretching iwell beyond the apical leaf of the vine.

“You see how long and fresh these are? That’s a sign the vine still is sending a lot of energy into growth,” she said. She grabbed another vine and noted the tendrils were starting to die back a little.

“This one is starting to focus its energy on producing fruit and not growth,” she said. “You can see how here we have flowers as well as clusters of green, pepper corn-size grapes.”

She paused and looked down the tidy rows, far different from the wild growth of recent years when vines went unclipped, still recovering from killing freezes in 2013 and 2014.

“It’s great to see the vineyard in shape and looking good,” she said. “Last year we hardly did any pruning at all and it was a jungle but this year John (Behrs, her husband and business partner) and the crews have been working almost constantly retraining and reshaping the vines.”