Archive

It was 40 years ago the American wine revolution occurred

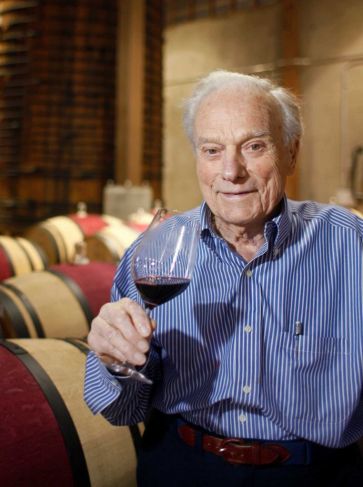

Warren Winiarski, whose 1973 Stag’s Leap Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon placed first among red wines at the 1976 Judgment of Paris, played a key role in the early days of the modern Colorado wine industry. To Winiarski’s right is Kyle Schlachter of the Colorado wine Industry Development Board.

A face familiar to Colorado winemakers is celebrating a 40th anniversary this year.

But it’s not your usual anniversary. This time it’s Warren Winiarski, the renowned California winemaker who nearly 50 years ago played midwife to a nascent Colorado wine industry, celebrating what is considered the most-consequential event in American winemaking.

Winiarski, the son of Polish immigrants and whose last name can be translated as “winemaker,” made the 1973 Stag’s Leap Cellars Cabernet Sauvignon that in 1976 bested the top red wines of France in a blind tasting that’s known as The Judgment of Paris.

At the same tasting, a 1973 Chateau Montelena Chardonnay made by Miljenko “Mike” Grgich won out against the best French white Burgundy.

This unexpected result in what was planned as a slam-dunk showing of the “best of the best” of the French wine industry at the expense of the upstart Americans stunned the wine world and put Napa Valley, and by extent the American wine industry, on the map.

May 24 marks the 40th anniversary of The Judgment of Paris and to commemorate the event, Winiarski and the Smithsonian are hosting in May two sold-out wine dinners.

The dinners will be held at the National Museum of American History and will bring together individuals who organized and attended the 1976 tasting in Paris, the winemakers who made the winning vintages, and individuals who are carrying on the legacy of fine winemaking in America.

Two other notable guests will be attending the events: wine writer Steven Spurrier, who arranged the competition, and George M. Taber, a Time magazine reporter and the only journalist to cover the event. Writer and wine critic W. Blake Gray called Taber’s four-paragraph story about the tasting “the most significant news story ever written about wine.”

At the time, however, no one realized how significant it was, least of all Winiarski.

He had been asked to submit a wine for the tasting but he was in Chicago, not Paris, on the day of the judging.

“I was in Chicago when Barbara (his wife) called me to say I had won,” recalled Winiarski during a recent conversation. “I said, ‘That’s nice.” I didn’t know what wines were being tasted or who the judges were.”

Once he realized the impact of what he and Grgich had accomplished, he says it “changed the way we looked at things.”

Meaning American winemakers, and back then it almost entirely was California, no longer had to play caddie to the European wine industry.

“Nothing was the same after that,” Winiarski said. “It certainly changed the way I looked at things and opened many horizons for me and the industry.”

It certainly angered and frustrated much of the French wine industry, Winarski recalled, including one French judge who demanded her ballots be returned.

“Afterwards I received several letters from members of the French wine industry saying that the results of the 1976 tasting were a fluke,” he said.

The 2008 movie “Bottle Shock,” which focuses more on Grgich’s chardonnay, is an interpretation of the judging.

A bottle of Winiarski’s award-winning 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon is displayed in the Smithsonian’s “FOOD: Transforming the American Table 1950-2000” exhibition.

In its November 2013 issue, Smithsonian magazine included this bottle as one of the “101 Objects That Made America.”

“I always was striving to achieve a sense of completeness, of balance, in my winemaking,” Winiarski said. “I think the wine that went to France reflected that balance.”

Winiarski was inducted into the California Vintners Hall of Fame in 2009.

CAVE brings new look to wine sampling events

There may be no better way develop a good foundation in the intricacies and intimacies of wines and winemaking than to visit wine regions, tour the wineries and meet the people behind the wines.

However, when you already live in a wine region, as do we in the Grand and North Fork valleys, the very proximity of wineries sometimes gets lost.

Just as you can glance at the skyline and see Grand Mesa without fully comprehending the beauty you see there, it’s easy to overlook the marvel of winemaking when it’s being done on a daily basis in your backyard.

Winemaker Bennett Price of DeBeque Canyon Winery in Palisade uses a wine “thief” to pull a sample during a recent Barrel into Spring tasting.

The wineries are there, and most are open year-round, it’s just a matter of us devoting the time to open the doors and walk in.

Maybe it takes a formal invitation, which is what the Grand Valley Winery Association has offered with its annual Barrel Into Spring wine tasting.

Seven local wineries open their wineries for two weekends (this year it’s April 23-24 and May 14-15) for winery tours, wine tastings and unique insights.

It’s a great opportunity to increase your wine knowledge and perhaps taste wines you’ll not taste otherwise.

But, and it’s a big one, Barrel Into Spring highlights only seven wineries and invariably sells out early. Because the event is very popular, and but to keep the weekend enjoyable for everyone, attendance and tickets are strictly limited.

This year tickets ($70 per weekend) went on sale Jan. 4 and were sold in a blink.

Now, though, you have another chance. The Colorado Association for Viticulture and Enology (CAVE), the same terrific folks who each September bring us Colorado Mountain Winefest, is introducing a statewide spring barrel tasting called A Taste of Spring. Read more…

Dreading tax season? It never ends for winemakers

Wines being aged in barrels or bottles are counted as produced wine but aren’t taxed until the wine is moved out of bond.

Readers of a certain age will recall a 1960s TV series called “The Untouchables” featuring Robert Stack as Elliot Ness, a Prohibition agent in Chicago in the late 1920s.

Ness, under the aegis of the then-Bureau of Prohibition, was credited with breaking mobster Al Capone’s hold on Chicago by destroying Capone’s extensive bootlegging network.

Photos of Ness and his hand-picked team smashing huge vats and beer tanks and pouring illicit booze out into the streets helped viewers forget Ness was not simply an axe-wielding, anti-alcohol Carry Nation but a federal tax agent, making a case against Capone for tax evasion.

Ness and Capone are gone but the feds, through the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), still keep a sharp eye on who pays their excise taxes.

Wines are taxed at state and federal levels at varying rates according to the wines’ alcohol-by-volume content (it’s similar for beer and spirits). The higher ABV, the higher tax per gallon. The rates goes from $1.07 a gallon (21 cents per .750 ml bottle) for wine with up to 14 percent ABV up to $3.15/gallon for wine with 21-24 percent ABV.

Wineries can either pay the taxes as they come due (see below) or post a bond, an insurance policy of sorts, against the tax bill.

Bonds are fairly cheap, as low as $100-$200 for the smallest wineries.

Excise taxes are due on wines when they become available for public consumption or purchase.

“The concept of a bond was the feds having some assurance you will pay your excise taxes,” said Bob Witham of Two Rivers Winery and Chateau on the Redlands.

Once a wine is “produced”, meaning fermentation is done, it is subject to excise tax. A winery doesn’t have to pay the tax until the wine is ready to be sold or consumed. By storing (aging) the wine in bottle or barrel in specially designated bonded areas, the winery can delay paying these taxes.

Once the wine moves out of the bonded area, which may be somewhere in the winery or an offsite storage unit, the excise taxes are due. Read more…

Mondavi and Tachis – A world apart yet not so different

It wasn’t until the obituaries were noted and carefully read that some fascinating parallels were revealed in the careers of winemakers Peter Mondavi and Giacomo Tachis.

Peter Mondavi, 1914-2016 (AP photo)

Two men separated by nearly two continents and 6,000 miles yet whose impacts on wine and winemaking will last far longer than many of the current winemakers.

Plus, the fact both were of Italian lineage cements a long-held belief that the world of wine owes much to its Italian heritage.

Mondavi died Feb. 19 at 101 and in early partnership with brother Robert, a remarkable winemaker in his own right who died in 2008, made their family-owned Charles Krug winery one of the early leaders in Napa Valley wine history.

According to several articles, Peter Mondavi adopted ideas he had learned while doing graduate at the University of California, Berkeley, to turn California from a general source for unremarkable wines into one of the world’s premier wine regions.

He’s said to have been the first Napa Valley winemaker to use cold fermentation and sterile filtration to produce crisp, fruity whites.

Also, his winery was the first in Napa Valley to use new French oak casks for aging and to adopt the uncommon (for then) practice of vintage-dating its varietal wines.

Such was his passion for winemaking, and even more his passion for protecting his family business, that he still going into the office at the age of 100.

The Charles Krug Winery, during this Golden Age of California cabernet, became famed for its well-structured and elegant Vintage Selection cabernets.

Giacomo Tachis, 1933-2016

Tachis, meanwhile, who died Feb. 5 at the age of 82 at his home in San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Tuscany, equally was known for his pioneering use of temperature-controlled fermentation and aging in oak barrels.

It once was said that there are two eras in the history of winemaking in Tuscany: before Giacomo Tachis and after Tachis.

One of Tachis’ most notable accomplishments was his role in using French grape varietals (notably cabernet sauvignon and cabernet franc) in developing what became known as “Super Tuscan” wines. There had been a few earlier experiments with using non-Italian grape varieties but it wasn’t until 1961, with the state of Chianti in sorry shape, when Tachis helped develop the Bordeaux-influenced, sangiovese-based Sassicaia (with Marchesi Incisi della Rocchetta), Tignanello (with Marchese Piero Antinori, whose family had been experimenting with cabernet blends since the 1920s) and Solaia, among them the first of the so-called Super Tuscan wines.

These wines with their French-grape components didn’t fit the restrictive Italian regulations and rather than be lumped with common and less-distinctive vino da tavola, the term Super Tuscan was developed.

“They opened the door to a new market — as well as the road to a better-quality wine — at a time when, especially in Tuscany, Chianti was a weak, cheap wine,” Giacomo Tachis told Decanter Magazine in 2003.

The wines lifted the reputation of all Italian wines, and while now some of the polish has worn off this so-called “international style,” it paved the way to success and worldwide markets for many Italian winemakers.

After Tachis was named Decanter magazine’s Man of the Year in 2011, wine expert Jancis Robinson wrote “Giacomo Tachis changed the style of Italian wine, dragging it – kicking and screaming – into the 20th century.

“And by changing the style of the wines, he changed the way in which they are perceived,” wrote Robinson. “Without him, Italian wine would not be as successful as it is today.”

Tachis, in his post-Antinori career, developed highly acclaimed and sought-after red wines in Sicily, Sardinia, and the Marches region of central Italy.

There was one notable difference between these two innovative winemakers, separated as they were by miles if not temperament and passion. While they almost simultaneously pioneered similar techniques (cold fermentation, oak aging) to improve what went into the bottle, they differed in what they put on the bottle.

Mondavi introduced the use of varietal labeling on wine while Tachis adopted less-descriptive labeling, thus perhaps starting the trend to fanciful labels on wines.

Two men, two imprints, and the world of wine made better.

A recent note from Giovanni Mantovani, General Director for Veronafiere, the site of the annual VinItaly wine exposition, said this year’s VinItaly, the 50th anniversary, will be dedicated to the legacy of Giacomo Tachis.

“Giacomo Tachis represented the renaissance of Italian wines and will remain forever in the history of Italian winemaking and in the hearts of those who knew him,” said Montovani in the announcement.